As I suspected, moving continents took its toll on the number of books I read this year, although this was balanced out by lots of uninterrupted reading time during our travels and I finished at a respectable 38. And if Robert reads this, I’m sure he will already be banging his head against a desk saying that I should be counting quality over quantity anyway. So without further ado, here was my 2019 in books:

Fiction

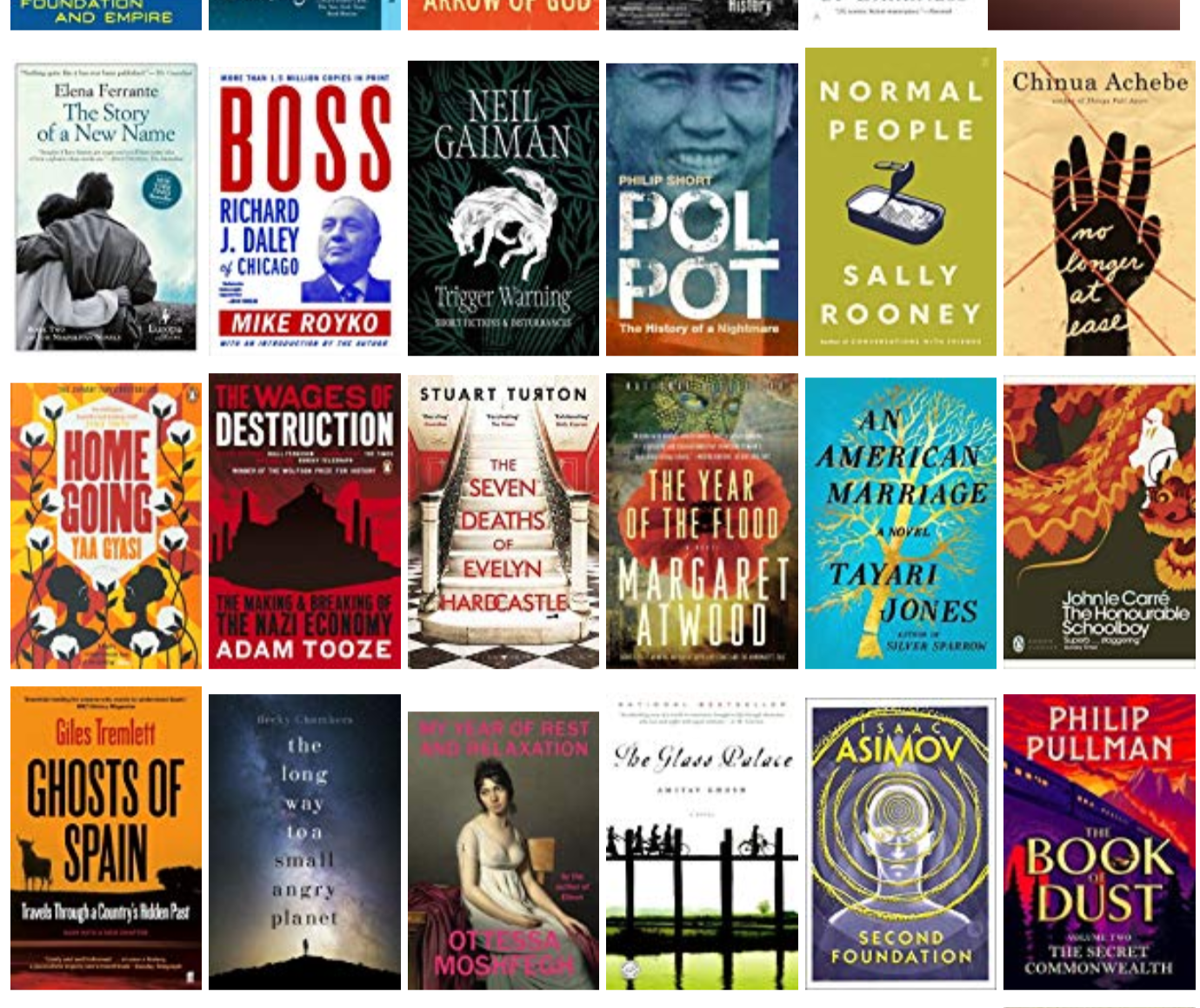

I began 2019 in fine style with The Goldfinch, the most recently-published of Donna Tartt’s three novels and, sadly, likely to remain that way for a couple of years yet at least. It’s a long book, but well paced, and I thought a lot about the characters in-between reading sessions – no doubt partly because we were hiking through Torres del Paine National Park at the time. I’ll never forget waiting for the catamaran when a big plot twist occured, or coming to the end of the story while lying in my sleeping bag on our last night of camping, just as raindrops began to gently pitter-patter on our tent. I was also pleased that the book ended with less despair than I thought it would, and once we got back to civilisation I really enjoyed looking up the eponymous goldfinch painting.

The Grapes of Wrath had been lying on my to-read shelf for years and I think I had built up a bit of a phobia of it, partly due to Mr. Buchanan’s volcanic demolition of the very idea of using it for my comparative AS English essay. In the end I was pleasantly surprised, and the combination of Steinbeck’s scenic descriptions and his characters’ distinctive dialects creates an extraordinarily vivid world. Whatever else you make it, the relationship between Tom and his Ma is quite beautiful. If I was feeling in an AS English-y mood, I might compare it favourably to the relationship between Ignatius and his mother in The Confederacy of Dunces, another classic American novel which I had procrastinated about reading but one I suspect Mr. Buchanan would have enjoyed rather more. It was Todd who recommended this to me, way back on one of the staircases to the 6th floor of the Groupon building in Chicago, and I’m glad I got there eventually because it is very funny. The spoilt, delusional Ignatius is an utterly compelling character – albeit repellent and obnoxious at the same time – although I’m afraid I’m the type of person who unequivocally wanted him to be captured at the end of the book rather than cheered on the exploits of the ultimate anti-hero.

When I got back to London I found that everyone was reading Normal People on the Tube, and as usual there is some wisdom in the crowd. This is an engaging novel which flits between the minds of Connell and Marianne like a fly, mostly avoiding big moments of drama in favour of the little things which make up a realistic teenage relationship. I loved the way it captured the complicated, not-one-thing-or-the-other type of bond which can only really form between two people at school but then stays with you forever. Another great novel about relationships this year was An American Marriage, the story of a relationship wrecked by a wrongful conviction and imprisonment. When reading this you really, really want everything to work out – why can’t everything just go back to the way it was? – but of course it can’t, no matter what the formal language of justice would say, and it’s a gut-punch.

When I read Celeste Ng’s Little Fires Everywhere last year I failed to write any notes, so after finishing Everything I Never Told You this year I was determined to remember a little more. I think my feelings towards both books are similar, though: I really enjoyed reading them, but I do struggle to believe in the characters. Would the sibling relationship between Nath and Lydia, for example, really blossom after years and years of being parented so differently? But these aren’t meant as criticisms, just… wonderings. I am happy to criticise Robert J. Sawyer’s Hybrids, though, the third of his Neanderthal Parallax trilogy which opened so well but is a classic case of putting all of the interesting ideas into the first book. By the end it’s the rather tedious religious question which becomes central to the plot: a shame, because it’s by far the least interesting part of the whole thing.

Conversely, I failed to love the first of Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan Novels last year but am so, so glad I kept going with The Story of a New Name in 2019. Essentially, the problem is that the author considers the whole thing to be one long novel, so the beginning is slow with a lot of build-up but by the start of the second book you can just get straight to the plot. The friendship between Lenù and Lila is an incredible literary creation and I can’t wait to see how it unfolds further next year.

In 2019 I also completed Chinua Achebe’s African Trilogy with Arrow of God and No Longer At Ease. I’ve totally stolen this point from the introduction, but it is true that it’s the metaphors and proverbs from Arrow of God which get inside your head after a while and make the biggest impression. The fact that the scenes from the perspective of the colonial administration were much easier for me to follow (with familiar-looking names that didn’t require any checks in the glossary) than those in the villages speaks volumes about having cultural reference points. Anyway once I got into this book I preferred it to the original Things Fall Apart. No Longer At Ease jumps forward to the late 1950s to when independence feels close and takes another look at cultural clash, this time between the push-and-pull of forces which lead a good man to accept a bribe and fall into corruption. These aren’t always easy books to read, but I’m glad I did.

I’ll tell you what: The Seven Deaths of Evelyn Hardcastle is amazing fun, and I’m very grateful to Katie for lending me this time-travelling, body-swapping murder mystery as I didn’t want to put it down until the puzzle was solved. Katie also recommended The Long Way to a Small Angry Planet which I have mixed feelings about. The characters are adorable, the inter-species worldbuilding is clever and thoughtful and I do appreciate that the unlikeable jerk on the ship happened to be named Corbin. (Jokes!) I just didn’t love the plot structure meandering between different standalone ‘incidents’ rather than a clear overriding narrative, although I will happily come back to the series for more. As for Neil Gaiman’s Trigger Warning – a collection of short stories – it was the book that came back to me for more, as when I fell asleep in Vietnam after reading one of his tales set on the Isle of Skye it promptly continued to unfold in my fevered nap-dream. It’s what Gaiman would have wanted, I guess?

All books in the sci-fi genre owe some sort of debt to Asimov, and this year I reached Foundation and Empire and Second Foundation in his Foundation series. This may be completely off-base, but when I picture the Second Foundationers quietly pulling the psychic strings of the universe behind the scenes it definitely makes me think of the bald guys from Fringe. I also read Ursula Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness which is surely a masterpiece of science fiction, and plunges into the cultural alienation of a visitor to a hermaphrodite species on a very cold planet. Unlike the Neathanderthal series there are no glaring chunks of exposition, but instead so many layers and so much to think about. Highly recommended.

Homegoing begins in an eighteenth century African village which becomes involved in the slave trade – not a perspective I can remember from a novel before, and it felt like discovering the missing first half of Octavia E Butler’s Kindred in the sense of better understanding where American slaves were taken from. Each chapter of the book then moves forward through the generations and between two different strands of the same family, which means that you only get a thin slice of each character. By the end the story had passed through so many lives that the earlier generations were just a hazy memory… which, in a sense, is just like real life. The ending of the book is perhaps a little neat and contrived, but otherwise I really enjoyed this.

Contrary to expectations, I also really got into My Year of Rest and Relaxation. If you simply describe the plot (wealthy New Yorker medicates herself to sleep for a year) it doesn’t sound very compelling at all, but the writing is incredibly engaging and completely sucked me in. It also helps that the book is fairly short and doesn’t overstay its welcome. Conversely, while it usually takes me a while to get into ‘epic’ multi-generational books like The Glass Palace, in this case I’m not sure I ever truly did. I don’t have any specific complaints (aside from the last few chapters where it felt like the author was rushing to lay out all of the remaining story) but it just never became as compelling as both the plot and the characters should warrant. That said, I did appreciate learning more of the history of Burma/Myanmar and was pleased when I kept recognising locations (Penang! Butterworth! Cameron Highlands!) from our travels.

The Year of a Flood is an excellent sequel to Oryx and Crake, although it’s actually more of a parallel retelling of the same events from other perspectives: this time, those of the masses in the ‘pleeblands’ and the environmentalist cult of God’s Gardeners. Atwood continues to build out her astonishingly well-developed world here, and my only frustration when reading it was that as Amanda had lent me her Oryx and Crake paperback I couldn’t go back to check the original references to the main characters! I certainly had no memory of Ren/Brenda at all, but although I believe that she only appears very fleetingly in the first book it is satisfying that her diary message for Jimmy exists in both to tie the plots together.

I also made a very welcome return to world of His Dark Materials with The Secret Commonwealth, the second installment of Philip Pullman’s new trilogy. From the very beginning, I was captivated (and devastated) by the notion of Lyra and Pan falling out and not talking to each other, and it was wonderful to see the world open up as the plot went on as Pullman pushes open the door wider than the very narrow story of the last book. That said, I don’t feel that he really nailed Lyra as a 20 year old: her philosophy doesn’t ring true given her own experiences in the original trilogy, and there are definitely some badly-handled sexual themes. It also ends at a sudden juncture mid-plot! Nonetheless, I did really enjoy it, and at the end of the year I snuck back into Pullman’s world one more time with Once Upon A Time In The North – a wonderful novella which tells of the first meeting between Lee Scoresby and Iorek Byrnison.

But my absolute standout favourite book of the year has to be Patrick Rothfuss’s The Name of the Wind. I remember very clearly the night in Motel Bar in Chicago when Teresa recommended this book to me back in 2016, and I finally started reading it during the Torres del Paine trek as I thought a fully-fledged fantasy novel would be well-suited for hiking and camping. I was rewarded with the first part of this classic and absorbing tale of the heroic Kvothe – seasoned, to be fair, with a fair dose of wish fulfilment – and after exercising a lot of willpower to avoid reading the sequel immediately, I am now very excited to return to the world of The Kingkiller Chronicles as soon as I can in 2020.

Non-Fiction

My first non-fiction book of the year was Atul Gawande’s Being Mortal about end-of-life care. It’s the kind of thing that we would benefit from discussing more openly within families before a crisis hits – indeed, that’s really Gawande’s whole point. He writes persuasively about the extent to which children will usually ‘choose safety’ and maximum medical intervention for their aging parents – even though they would usually prefer freedom and independence for themselves – although this does glide a little too easily over what happens with mental as well as physical decline. You probably won’t be super-excited to pick up this book, but it’s worth thinking about.

On a much lighter note, Time Travel: A History is a very well-written guide to the concept of time travel and its history across science, literature and culture. But it’s also written in an unnecessarily acerbic tone, and rather disdainful of a genre that so many people could have written about with a lot of love. I loved reading it – because I love time travel! – but I could have done with a friendlier guide. G.H. Hardy is much more enthusiastic about his chosen subject, mathematics, in his very short classic A Mathematician’s Apology. I decided to read this after seeing a play about Hardy and Ramanujan in Chicago and it’s a difficult book to review, but given its length it is well worth giving it a go.

The first chapter of Boss, Mike Royko’s classic text about longtime Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley, brought me vividly back to the city with its descriptions of its architecture and, sadly, its horrible freeways. Everyone knows that Chicago’s machine politics is ugly and corrupt – and this book will only confirm how depressing the city’s history is – although shortly after I finished it the city did elect a black, female and lesbian mayor so, even though a figurehead is not everything, that did feel like… something.

Giles Tremlett’s Ghosts of Spain was OK, but just OK. I read it because I wanted to learn a little more about modern Spanish history, and now I do understand a little more about modern Spanish history – especially the ongoing ghosts of the Civil War – so that was useful enough. For some reason I just didn’t love his writing style. And although it’s probably unfair to mention this one tiny thing, his use of the word ‘poetess’ at one point made me cringe. Punch and Judy Politics was perhaps exactly the opposite. I didn’t really need to learn anything about Prime Minister’s Questions – who does? – and the reason the authors can get so many gossipy interviews about it is because almost everything that happens in PMQs becomes unimportant immediately. But gossip is fun, obviously, and there were one or two insights into contemporary politicians which I found to be very revealing.

Parliament has changed a lot since the rule of King James VI/I, and yet – as ever – reading his Political Writings will throw up oddly modern moments. James was King of both England and Scotland as two separate countries, and although his speeches urging unification were ignored, reading them gave me a bit of a tingling feeling given how close to the end of said union it now feels that we are. On other topics, James has the force of conviction you would expect from a monarch whose principal position is the divine right of kings. For example, he advises his son not to duel, not to allow guns at court and not to believe that rhyming is the most important part of poetry, which to my mind is all pretty good advice. But he also instructs him to eat plenty of meat without any sauce – because sauces are somehow decadent – which is what comes from being King and never having anyone turn around and tell you to stop talking and just give the sauce a try. He’s pro-bridges, pro-roads, pro-schools and pro-hospitals but also anti-pubs and – amusingly – anti-London, which he thinks is too big and too powerful. “Even so now in England, all the country is gotten into London; so as with time, England will only be London, and the whole country will be left waste,” he complains. You may have heard that before.

Finally, two horrors of the twentieth century are explored in Adam Tooze’s The Making and Breaking of the Nazi Economy and Philip Short’s Pol Pot: The History of a Nightmare. Tooze has the more honest title – this really is a book about the Nazi economy rather than a general history – and the overriding message is not only that Nazi Germany was completely outmatched in economic and industrial production during WW2 (especially once the US joined the war) but that its leaders knew this full well. And yet they ploughed ahead anyway, in the spirit of “the gap is only going to widen”, with predictable results. The statistical focus makes the narrative a bit of a slog to get through at times, but it’s a memorable analysis and there are some truly illuminating moments when the horrific contradictions of Nazi war aims (for example, extermination versus slave labour) are brought into direct conflict with each other. If you only have a casual interest, this is probably one to file under “find a good podcast about instead”.

In comparison to Nazi Germany, Pol Pot’s Khmer Rouge regime in Cambodia is only glancingly mentioned in modern British culture, so after visiting the Genocide Museum in Phnom Penh I felt compelled to start reading up on it immediately. Like all civil wars it’s a complicated story – much more complicated than any story told through the simple “West vs. USSR” schema. I said that Short’s title was less honest because this is not really a book about Pol Pot himself, but rather the whole painful story of how Cambodia came to be ruled by what began in the 1950s as a rather hare-brained Parisian student group but went on to seize power and then murder nearly a quarter of Cambodia’s entire population. It’s never a good idea to try and rank atrocities alongside each other, but there are certain aspects of the Khmer Rouge regime that were so extreme and so crazy – their abolition of currency, their forced evacuation of the entire capital city for the countryside – that make them particularly grimly fascinating. Short’s book is a perfectly good guide, but however you choose to learn about it this is an awful but compelling part of our very recent global history.