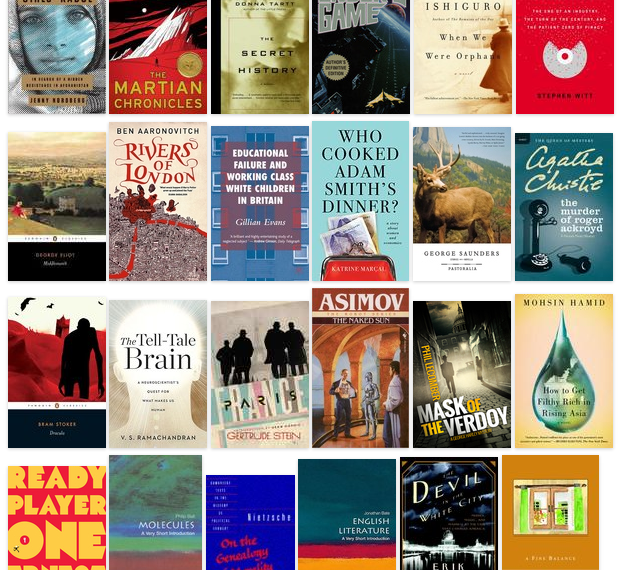

After a dip in 2014, this year I returned to my upward curve for number of books read. And yes, while caring about the raw number is silly, it’s also a good motivator to do something I really enjoy but otherwise struggle to make time for. And I read some great things in 2015…

I’ve seen plenty of interesting authors interviewed about their books on The Daily Show over the years, but I rarely manage to follow-up by reading them. Something about Bryan Stevenson was compelling enough to buck this trend, and his account of working as a lawyer to overturn horrendous miscarriages of justice in the American South – Just Mercy – was one of the most powerful and important things I read this year. It’s about a whole lot more than the death penalty, but the image of a prison officer strapping a defenceless human being into a chair and executing him – at the behest of the state – is one of the most jarring and frightening intrusions of barbarism into the modern world I can imagine. I think there is validity to the argument that we over-praise democracy and under-appreciate the rule of law, and in a world where entirely innocent people can be arrested, convicted, imprisoned and killed, both are denied.

Another Daily Show recommendation was The Underground Girls of Kabul, which tells the fascinating story of bacha posh: girls raised as boys, at least until adolescence, for both ‘luck’ and raw practicality in cultures where being born female is so bad it can make your mother weep. A useful reminder both of the constructed nature of gender, and the hidden adaptations and compromises which ‘real people’ always make below the surface of a society. Another book about being born in the wrong place at the wrong time was the classic There Are No Children Here (a gift from Robert) which follows two young boys growing up in Chicago’s prison of poverty and violence. It’s really not far away. And in turn, Educational Failure and White Working Class Children in Britain (Tash’s recommendation from years ago) well articulates social class in Britain, which can be hard to explain to people here.

On a more upbeat note, Rivers of London – recommended by Diamond Geezer a few times on his blog – was a rough but promising Gaiman-esque urban fantasy, and sets up an intriguing series to follow. Ready Player One was even more fun: a page-turning young adult adventure which appealed to someone with only conversational fluency in 1980s pop culture. It certainly left me more uplifted than the similar Ender’s Game, which others feel passionately about, and is a good read but also surprisingly chilling and sad. I am a little intrigued to see what happens next, but I won’t be rushing. It’s the same story with Mark of the Verdoy, which attempts to kick off a series of 1930s London detective stories, but wears its amateur historian heart a little too closely on its sleeve. (Please don’t put dialogue into Ramsay MacDonald’s mouth unless you really know what you’re dong.)

A few books were return visits to worlds from previous years. I’ve loved all of JK Rowling’s Cormoran Strike series, but the third entry – Career of Evil – improved on its predecessors with a satisfying ending to the murder plot as well as the usual enjoyment of being among Robin and Strike. In the same vein, I very much enjoyed Agatha Christie’s fiendishly clever ending to The Murder of Roger Ackroyd. Something Fresh was my first non-Jeeves PG Wodehouse book, and while it didn’t make me laugh quite as much, I will certainly be back for more. Asimov’s The Naked Sun, the second in his Robot series, was better than the first and sketched a memorable portrait of an elite society with a crippling phobia of human contact. My other classic sci-fi of the year, Ray Bradbury’s collection of short interlinked stories The Martian Chronicles (thanks, Katie!), was also wonderfully alien and spooky. I’ll be back for more of him, too.

I had put off reading Dracula for years, but it was surprisingly fluid and gripping, at least for most of the way through. The much-discussed ‘undertones’ of Victorian sexual fears are not so much undertones as raw panic – at one point sweet, wholesome Mina is forced to her knees to suck Dracula’s blood out from his chest while her humiliated husband lies unconscious – but you didn’t expect today’s mores from the granddaddy of nineteenth century Gothic horror, did you? At least Mina has a pretty happy relationship when she’s not being drained to death. The experience of Dorothea in Middlemarch, by contrast, is a sad reminder of the Victorian ‘cross your fingers and hope for the best’ approach to marriage for women. I was more enthralled than I expected to be by George Eliot’s long but well-paced classic on provincial life. And then every so often I would pause to give sincere thanks for dating and contraception.

This year I also got around to Crime and Punishment. No doubt Dostoevsky is masterful at getting under the skin of his jumpy and degenerating protagonist, Raskolnikov, but he also hits you in the face with Christian salvation a little too much for my liking. And most of said salvation is delivered by poor Sonya, who becomes inexplicably devoted to her best friend’s murderer. (She’s a prostitute, so her devotion to others is supposed to act as her own redemption, except today it’s hard to conjure up any feelings of condemnation and so she becomes purely a martyr.)

Two American novels which Robert and Todd both suggested – Jonathan Franzen’s Freedom and Donna Tartt’s The Secret History – were both great. The Secret History is the greater of the two, I think, mostly because I was successfully ensnared into mentally egging on the murder before being dumped with real feelings of horror and guilt afterwards. Freedom has become hazier in my mind over the year, although I do remember thinking it shared a literary style with Zadie Smith. And Pastoralia, George Saunders’s collection of brisk (and often weird) short stories satirising modern life, was another recommendation (thanks, Katie Schuering!) I will gladly pass on to others. Gertrude Stein’s Paris France was also odd but breezy: like going to lunch at a café with an eccentric aunt, whose observations on life are mostly ludicrous but pleasant enough to listen to for a bit. On the other hand, The Fortress of Solitude – a Brooklyn-based coming-of-age story – was more of a slog.

In the late nineteenth century, in Chicago, Herman Webster Mudgett built a hotel to host visitors to the Chicago World’s Fair. The ‘castle’ took up an entire block and was designed to be as confusing as possible: a maze of rooms at odd angles with staircases leading to nowhere and doors which could only be opened from one side. The whole point was to allow Mudgett, also known as H.H. Holmes, to murder young women who visited from out of town, several of whom he married first. The story of H.H. Holmes is, without doubt, the only reason anyone ever picks up The Devil In The White City. That it is intertwined with a moderately-interesting account of the design and construction of the World’s Fair itself will be either a pleasant surprise or an annoying deviation, depending on taste.

Some short takes: When We Were Orphans is no one’s favourite Ishiguro novel (least of all his) and threw me into a bit of a funk when reading it, but a bad Ishiguro book is still a pretty good book. Who Cooked Adam Smith’s Dinner? (answer: his unpaid mother) is a witty, feminist critique of homo economicus. I suspect the author would appreciate the themes of maternal self-sacrifice in Please Look After Mom, partly notable for being written in the second person. I chose The Tell-Tale Brain as a follow-up to Phantoms of the Brain, which I read years ago, and if you decide to join me you will spend days trying to shoehorn interesting neurological studies into unrelated conversations. I’ve read numerous variations of the Asian rags-to-riches-to-rags story which is told in How To Get Filthy Rich In Rising Asia, but this is a good and moving one. A Fine Balance, set during India’s ‘Emergency’ period of the mid-1970s, is a more demanding read but also a beautiful, sad story with wonderful and memorable characters. I grew very attached.

Finally, while it’s a terrible cliché to enjoy Nietzsche, it is very hard not to. He’s sharp and insightful, weaving a great historical narrative out of clever linguistic details (e.g. what is ‘good/evil’, and how does it differ from ‘good/bad’?) and, when he gets worked up, he can hold one hell of a shouting match with himself. One thing Nietzsche can’t do, however, is hold a candle to George Orwell. And so I want to conclude this lengthy review with praise for him, who can be enjoyed in Penguin’s collection of essays. Orwell possessed such a wise, prophetic and independent voice that he is admired and respected – without misrepresentation – by both the left and the right. But you should know, if you’ve only read his famous novels, that Orwell does a marvellous line in cultural history. He cares about comic books, murder mysteries and cooking – and he cares about how, and why, they change over time. He understands patriotism, understands how people think and behave (just read, for example, his description of which books are borrowed from libraries versus which books are bought from bookshops) and he does it in the finest, clearest prose. For Orwell, good writing is a political act, and he makes me feel illiterate. I wish he were still around to consult.

Lucy Mason, Stephanie Francesca Pereira liked this post.